Blog: Lucy Peacock

Trespass

I should not know

that the grass that grows

on the other side of the barbed wire fence

really is more green.

I should not have seen

the place, where in between

the rocks grow orchids, like a forest

of tiny, curling trees.

And I should not have been

to the very top of the steepest field

before climbing down

on hands and heels.

These are my trespasses.

Forgive me.

Work in progress performed at Wirksworth Art & Architecture Trail

Harborough Rocks

6am is not a time I usually see on a Saturday. But this weekend the weather forecast is good, and I want to see the morning light at Harborough Rocks at the top of the Hill. So my son and I climb bleary-eyed into the car and drive up to the little rough patch at the side of the road near the factory. Ours is the only car here.

As we walk up to the rocks I'm conscious of the sounds. There are fewer sounds than normal: there's no traffic, and no walkers or cyclists, but that just makes the hum of the factory seem louder. And above that hum is the sound of birds, all heartily singing their different songs.

I know this place. We've walked here often, and sometimes I bring the children so they can climb the rocks and play in the cave. But I've never seen it like this. Our shadows fall in the wrong direction. Our feet are soaked in dew. And the air is even fresher than it usually is.

We're in sunshine, though the blades of the nearby turbines dance in and out of the morning mist. And at the top of the rocks, despite the noise, it's peaceful.

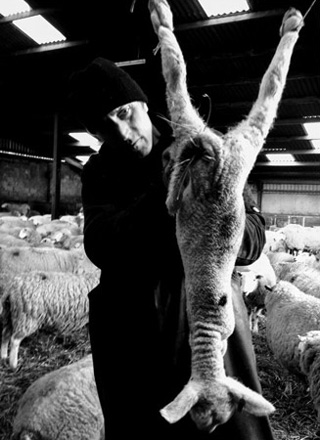

Ian Lomas, Skinning a dead lamb.

Early morning at Griffe Walk

Lambs

In the barn,

in straw stained with afterbirth,

the ewes gather

as they wait

for the forces inside

to bring new life.

A ewe walks in circles as she labours. In her movements there's fear, and there's fear too in the cries of the ewes that labour beside her.

It's been too long.

She tries to run as they pull her to the ground, but they hold her firmly as Ian pulls the lamb from her body, and she is released.

These are the moments when

life is most fragile.

When a swing by the legs,

or a helping breath

can be the difference

between spluttering life

and death.

With quiet precision,

Ian cuts the skin from

a stillborn lamb.

And now wearing that skin,

a motherless lamb

can feed from

the lambless ewe.

Hopton-Wood Stone

Hopton-Wood Stone was quarried and later mined around Middleton until 1995. It was famous for its exceptional purity and the fact that it could be quarried in large blocks.

In 1920, the Imperial War Graves Commission commisioned headstones for the First World War cemetaries in Europe. For the following 6 years, Middleton supplied 300 headstones per week, polished and engraved with the name of a soldier. Some of Middleton's headstones can be seen at Lijssthenhoek Military Cemetery, near Ypres. And if you look carefully, you can sometimes see the headstones that were rejected in the houses around the village, as in the picture below.

"Mankind" by Eric Gill, in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

"Mankind" by Eric Gill, in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Window heads and a sill

Window heads and a sill

Working in Middleton Mine

This is an extract from an interview with John Doxey, about his work in Middleton Mine.

I enjoyed working in the mine. I worked on a twin boom rig that was converted from a dump truck at the saw mills in Middleton.

There'd be two of us on the drill rig, and we'd usually drill three holes - a threble. They'd set the holes for the explosions, and then set all three off together. It made a good heap of stone, which would be taken to the crusher. Afterwards, they loaded it onto the trains that would come up two or three times a day from Bolehill. The trains would take the stone down to the yard near Cromford cemetery [now Steeple Grange Light Railway], and then down to Cromford bottom, and away they went.

There were many different roads in the mine. There might have been five or six different headings with all those threbles in. Then we'd do the same further on, but we'd leave a piece about 25 yards square, and that took the weight of the roof.

There were two levels - there was a top level, which was taken out first. Then there's a level underneath, which you used to get to by turning right at the top of the hill as you went in. Then eventually afterwards we started taking the middle bit out as well, so instead of two 30ft high tunnels, it'd be 100ft high in places. That hill - it's standing on legs.

About the Hill

The hill of the project title rises to the north of Wirksworth, Derbyshire, and runs west and northwards to join the limestone plateau of the White Peak.

This part of the hill that we're exploring is not in the Peak District, but then the Peak District boundaries seem to have been determined more by industry than geology. Here, industry is everywhere: from the huge quarries to the anonymous cages that cap narrow old shafts from nobody knows when.

Here and there are the factories that process the parts of the hill: great monuments of steel and concrete standing alone in the rugged landscape. Stone from the quarries is still processed here. The minerals are imported now, though many still remain in the caverns and tunnels beneath the factory floor.

In the quarry faces you can see the marks of geological time - thick lines of limestone, formed over eons, and thinner, darker lines of volcanish ash. Fossils are everywhere - in the old quarries, such as the one at the National Stone Centre, you can find hundreds of them together, like carvings in the rock.

That limestone has been used all over the UK. The famous Hopton-Wood Stone from Middleton Mine has been used for buildings around the country including the Houses of Parliament, and was carved into thousands of headstones for the First World War graves in Europe. The mine lies empty now, but its enormous tunnels - 30m high in places - permeate the hill. "That hill is on legs," as local ex-mine worker John Doxey put it.

The railway that used to carry the stone from the quarries to the canal at Cromford is now the High Peak Trail. It carries walkers and cyclists up through the woods and then along the hill, past engine houses, wind turbines, stone-walled fields and those odd factories that seem to have come from another place. They all greet you as you walk along.

It is an amazing place, and I feel lucky to live here.

Read the latest blog posts by