Blog: Kate Bellis

HILL from the Air

Kate is working with drone pilot Nick Fisher to produce some large scale colour images of the Hill from above that will be shown alongside her black and white documentary images for HILL For bigger versions of these pictures, see our Facebook page

Harboro Rocks, Cave and Well from the Air

Harboro Rocks, Cave and Well from the Air

Harboro Rocks from the air, Climbers

Harboro Rocks from the air, Climbers

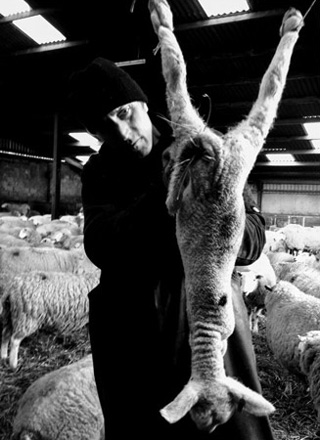

Psychobilly Shepherd

Ian Lomas was a Psychobilly* Rocker in his young wild days. From the Mosh pit to the slurry pit at Griffe Walk is quite a journey I think as I watch him skilfully, carefully switch a triplet lamb onto a ewe that has given birth but has nothing to show for it. This has to be done the instant the newborn drops, aquatic wet, bloodied and steaming onto the straw. It's birth Mother is busy talking and licking her other two lambs. He picks the slippery, stretched streak of new life up and drops it in a hush and rush of afterbirth and steam, oozing, wriggling behind it's new foster ewe. She turns and looks, a moments hesitation, then she greets her new lamb with a nuzzle, then a lick and she starts to talk in short quick breaths and rhythms to this, her lamb. Where else could it have come from, so wet and new? Neither birth Mother or foster Mother seem to notice the switch as Ian watches quietly, to make sure all goes well and as it should.

A few mornings later I am back in the lambing shed, Ian is milking and I Keep an eye while he is busy, But when I arrive there is a still born lamb. I go over quickly, trying not to disrupt the sleeping, waiting ewes. The lamb is still warm so I check its airway, rub it down with straw and swing it, nothing, the lambs Mother watches. Frustrated that life is not coming back this time, I stop my efforts after a while. But the watching ewe does not. I fall away, backing off in my failure. She comes forward to her dead lamb and begins to paw it where it's lungs could wheeze and splutter it back to life. She's not giving up, I photograph her quietly as she nuzzles, licks and paws at her lamb. Her eyes hold something that's hard to watch, but I am very lucky to witness. Still she will not give up, this is her first lamb, her only lamb, until that Psychobilly Shepherd finishes his milking shift and can again trick nature. Skinning her dead lamb and putting it's lifeless coat on a new body that is warm, pulsing and hungry, blaating for life and that ewes milk. 'The Clubfoot', Londons Rocking heartbeat in the 80's, never saw these things that happen on this Hill, these heartbeats that stop and sometimes start again.

Kate Bellis

*Psychobilly, Music that blends Punk Rock and Rockabilly.

Afterthought....

I didn't know until later, discussed over a cup of tea in the farm kitchen, that Ian lambed this ewe before I arrived that morning, he left the lamb alive to start milking the herd. Half an hour later he checks on the ewes and the lamb is dead. He's cross with himself for that, for not staying an extra five minutes when the dairy herd demanded milking. As he eats his breakfast he checks on Twitter, the frustrations and thoughts of other shepherds on other Hills.

Ian and John after milking, Ian's two weeks into night lambings, 6am Griffe Walk dairy.

LIGHT

Well here it is, I'm being laughed at again, which I deserve. There's amusement because I never quite make dawn which is at 5.30 am at this time of the year. My old car usually finds its way to Griffe Walk around 6 am. There's a good reason for my timing, the light that hits this grey block shed at around 6.30 am, in the cold early morning, is a gift. Ian's been up every night for two weeks and John Bowler, who helps with the milking, has been here since the shrinking blackness of predawn. It's hard for them to get excited about what I'm seeing, but I almost hold my breath, just in case it drifts into black again like the dust that's tumbled in that light now.

They go to let the cows out and check the other lambing shed, I'm left to keep an eye in here. Sally is with me, HILL's sculptor, she sits on the water trough and watches the light too, I can hear her pencil move on paper. There's a ewe lambing and she's chosen her spot, pawing the ground, right in this biblical slant of light. She is doing her job so well, she doesn't need me to interfere. The first lamb slithers into existence, out of its mother and twists of steam climb from its warm, new body. She is up then talking to her lamb, licking the mucus from its nose, the first communication is something special. Again she gets down and on with the job of creation and her next lamb. The light stays with us all the time, pulling the steam upwards in coils as the second lamb is born easily in front of me. I help clear the mucus from this ones nose as its mother is busy licking and talking to her first. Then, with fingers sticky with afterbirth, I photograph, quietly stealing those images out of the light.

During the night lambings, in the drowsy, dark shed, Ian knows when a ewe has lambed because he can hear this 'talking' between the ewe and her newborn.

Quarry

I'm crouched under the belly of this Beast, like a cowardly knight, waiting for it to wake up and devour me whole. But this Leviathan slumbers on, only the skill of the engineering team will wake it up, the conveyer belt had busted that morning, just before my first visit to Longcliffe Quarry.

Cleaning under the conveyer

I am kneeling in the limestone dust under the conveyer, it's so fine, like volcanic ash. Around me work half a dozen quarry workers, they've been sent to shovel out this stone powder while the beast slumbers. One, troglodyte like, is kneeling in the semi dark, it's awkward to shovel like that I think, but he gives me time and talks to me and laughs a bit. This technical malfunction is good for me, I can get up close and get some good working shots.

I climb now upwards along the metal spine and into the belly, following my guide, who works with the blasting team. This is where the conveyer is being fixed, the engineer works quickly, they're losing time and money. Sparks fly out, new rivets glow like polished gems in this dark centre. It's a strange environment, metallic and alien to me, I photograph quickly and get my shot, the engineer shrouded in his protective gear, doesn't hear me leave as metal grinds on metal. Light floods his workplace briefly as I step out from the dark.

This is a fragmented landscape, stripped bare to its ancient layers. My eyes time travel down through this Hill, the siren calls out, then a rumble, deep and primitive echoes through my chest. The layers fold and crumble in front of me, dust rolls like waves from the blast and the Hill gives us it's limestone treasure for toothpaste and a thousand other things we want and need.

After Blast Landscape

Stone and Bone

Stone and Bone were always here, on this Hill.

A child buried with love long ago.

The urn and contents now removed

To some museum store.

I watch my Son teasing his shadow on the back wall of Harboro' Cave. He twists and dances with it, balancing on one leg on the eon smooth boulders that crouch down on the cave floor. Arms up, he does 'bunny ears'; leg up arm thrust out, then there is a Dragon of sorts.

I close my eyes against the sword of Autumn light that slants so strongly into the cave at this time of year. When I do, I can still see my Son, shadow dancing at the back of my iris, my brain and eye echoing this intensity of light and dark. I open my eyes again and there he is, skipping between two worlds.

I photograph him with a ghost dog barking at his feet, but this is a light trick, it is a strange shadow cast by one of the boulders he hops on and off. I capture this image in this World, as this boy of mine plays with a shadow dog from another place and time of his imaginings.

Descent into Golconda Mine

I am spinning slowly on my thread of survival. Harnessed to a rope, I am descending 360 feet away from the iris of light above my head and down under the Hill into Golconda.

On the surface, shivering with cold, or something else, I'd photographed the mine research team disappear into this impossible man hole, a vertical door to a strange world I had no real knowledge of. I was in full denial that I was going through that breath stealing door too. I just kept on photographing on the surface of the Hill, in the light, it's what I do. There was only myself, the winch operator, and Andrew our expert guide, left on the surface. Lucy, Hill's poet, has gone down ahead, smiling through gritted teeth.

Now I am very alive, as I drop into the darkness and begin to spin slowly. My adrenalin has told me to breathe and has woken me from my denial daze and my mind watches, oh so very carefully, my descent with a survivors alertness. My head torch lights the chisel marks of the miners who dug this impossible hole. How? When? I wonder and spin slowly. There are rough candle niches in the walls that would have given a little light on their descent to this other world, old and rotten bits of wooden ladder, a platform and a tunnel leading away into that deep darkness. I move my head to see these clues of human industry and I spin again because of this small movement, my body bangs into the stone walls that hold these secrets. I am not cold now and I spin and drop and look and smell. It smells very old, primeval, metallic wet in my dry mouth.

I hear voices below me now and the shaft opens out into a larger chamber. My feet touch the rickety platform, 360 feet under the Hill - but still 60 feet from the bottom. I am to learn that this was the easy bit.

The start of the descent into Golconda

Lucy, Hill's Poet, at Golconda Mine's entrance

Lambing 2016

The track to Griffe Walk Farm is long and rough. It's just after dawn on a cold April morning. I pass a car parked up by the cattle grid and wonder about it: looks like it's been there all night long, it's all frosted up and the first splinters of sunlight are streaking through the ice fragmented glass. I drive up through the farmyard and park up by the old farm house, a ewe blaats at me from behind a wall, work dogs bark and that streaking early sun is just hitting the solid grey front of the house.

I haven't made it here for dawn though and I said to Ian I would. I walk down to the lambing shed where I find Ian with his Sister Carol lambing a ewe. It was her car that I drove past then, to save it's suspension from the track, left abandoned to a dark frosty night. They both quietly kneel, bringing new life into the world, Brother and Sister working together, Carol says that this is where she needed to be, with someone she loves, bringing new life to Griffe Walk. A rhythm of this old place, like the panting ewe they're helping now, bringing that skinny, stretched, streak of life out of the dark into the steaming bloodied barn. It's lit like a Church in that morning light.

"You're late, didn't make dawn then!" Ian says to me when he's finished lambing the ewe. He and Carol smile and chat even though they must be tired to the bone.

"No" I say, ashamed of my attachment to my warm bed and duvet that cold morning. "I didn't make dawn but I did raise my teacup to you as I had my cuppa and looked over the Hill from home. Look at the light in the barn now though!"

Ian laughs a little at me for that, I guess when you've been up all night dealing with life and death, blood muck and afterbirth, rats running over your boots, it must be very strange having me arrive and talk about the beauty of the light in this place.

Kate Bellis

Ian Lomas, Skinning a dead lamb to put the hide on a foster lamb, Griffe Walk Farm

Inside the shed in the early morning

Ian and Carol lambing

Read the latest blog posts by