Blog: Carol Fieldhouse

Sound sketches

Winter at Harborough

Stark, brooding land skinned of trees by altitude and weather.

Tough, yellowed grass gives way to crowning rocks. The wind whipped crags mellow briefly in the low sun's light. Old snowdrifts fade slowly behind the windswept, tumbled walls of the ancient land enclosures that fade more slowly still.

The theme for this Winter sound snippet was developed through vocal improvisation in response to/over one of Gavin's first films at Harborough that explored the gradual transition from deep underground up to the surface. The consideration was to keep it sparse and with an elemental quality in order to leave space for the unraveling of the film's own narrative.

Spring

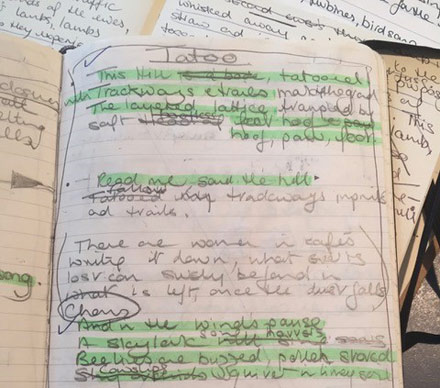

The hill endures

Its resonance, deep plundered, its pitted surface heals

Tattooed with timeless pathways, coffin roads and cattle tracks

And in the winds pause the skylark soars

Bee lines are buzzed, pollen stored

Hopeful cowslips, shy orchids bloom

Winter torrents subside through caverns below tombs

This theme is related to the Winter theme using similar melodic intervals but switching to a major key, giving a more uplifting sound suggesting a sense of opening, unfurling and a feeling of delight in the first warmth of the sun after Winter

Lambing at Griffe Farm

Extract from journal

An unexpected, wide valley opens out from the difficult to find track through and beyond the Sebelco Factory on the moor. The valley is hidden on all sides by its flanks from all but the handful of farms within it and any determined walker. Griffe farm, orientated with old knowledge of prevailing winds and weather, nestles in the lea of the outcrop of Harborough Rocks.

Arriving - the grim sight of the lost sheep for whom birthing was their last endeavour. Beyond this, Lambing Shed 1 is filled with ewes awaiting their single lamb, like low lying islands in a deep sea of straw. A palpable shared expectancy. Lambing Shed 2 has, and expects, multiple births. The atmosphere is hushed except for the whirring generator and each ewe wickering to its newborn followed in time by the tremulous bleat as the lamb experiences and employs air. The farmer, Ian, speaks softly, offering insight into his lambing life of twenty-hour days while almost imperceptibly maintaining his complete concentration on the needs of each of his flock. His deft hands, with minimum interference, assist the ewes when needed.

Two ewes deliver triplets either side of me in the space of 30 minutes. The third lamb of one ewe is yellowish in colour - a mark, Ian says that 'she had trouble with it.' Ian was ready, as the lamb dropped, he whisked it away and, almost in one movement, with no fuss, tossed it gently to the hindquarters of a lamb-less ewe in a pen. Within minutes the lamb was accepted.

The metre of the third theme was suggested by an extract of Lucy's Lambing poem and shaped by my own experience of witnessing the early morning in the Lambing Shed. I wanted the theme to carry something of my overriding impressions of this primal process that encompass; expectancy, waiting, more waiting and then the sudden urgent flurry of movement, positioning and imminent transition to the swift and momentous moment of birth. The process reminds me of a long running wave starting from a far distant storm and approaching the shore; there's no stopping it, it has an inevitability that will reach its conclusion.

Listening to a recording I made of a wickering ewe - a kind of gutterall tut tutting - I improvised vocally using Lucy's words before going to the piano to develop the idea. All three themes at the moment seem to have the defining characteristic of employing the fourth interval in the melody. This interval gives a particularly open, sometimes plaintive, potentially bleak sound that for me seems fitting with the atmosphere of the higher landscapes of the Hill.

from the Via Gellia to Griffe Farm

From the lay-by on the Via Gellia a barely visible path disappears up hill into a breach in the high limestone cliffs that line the road. The first impression is the smell of wild garlic carpeting the ground and beginning to decay, making the path slippery and pungent. The day is hot, 29 degrees centigrade, but in the shade of the extraordinarily tall trees reaching for the light from this deep cleft in the limestone plateau, it is cooler. The trees, and perhaps an imperceptible bend in the path, silences the traffic noise from the road below and there is just birdsong, occasional scuffles in the undergrowth and the lazy summer intermittent sound of buzzing insects. The path is rocky and wet underneath the garlic and would no doubt become a torrent in Winter with water running off the moor and continuing the valley's formation. Only dappled light penetrates to the floor of the wood and moss smothers stones and fallen trees. The steep sides of the narrow valley amplifies the birdsong.

Quite suddenly we reach the moor and the sounds change as dramatically as the physical landscape; a skylark hovers, ewes and lambs graze and call while a single dragonfly darts among the dry grasses in hot sun.

Wigber Low

A little further west from Harborough is Wigber Low, the rocky mound above Havenhill Brook by Bradbourne and the site of some of the last Anglo-Saxon pagan burials in the 7th Century; a site where people had been burying their dead for 2000 years before this. Four of these five burials were women. One in particular was buried with an arrowhead by her depicting a warrior, also what had been a leg of meat was across her left thigh marking her as a provider of high status and finally a long-decayed wooden purse with a bronze strip was attached to her belt. Relatively soon after these pagan burials were taking place, and just across the narrow Havenhill Brook, an early 8th Christian Cross was being erected in the settlement of Bradbourne. This account, found in Bill Bevan's book Walk Into The Dark Ages (2014), offers an account of an extraordinary sequence of transition set in this precise landscape; it underlines the remarkable and varied ways the land has been at the heart of belief systems and is echoed still in the people who continue to honour these ancient sacred places.

Walking from Bradbourne down through Havenhill Brook Dale and up trackways ancient and more recent, I'm struck by the tiny wizened thorn tree clinging to the stones of the Low. On a sunny day it is still a desolate spot in the chilling wind.

Harborough Cave

The changing nature of the Harborough cave, a haven from the piercing January cold of the Easterly wind driven sleet at 300 metres. A cave tucked in the lea of the low rise rocky outcrop above the high limestone plateau of West Derbyshire. Low light gloom and fragmented rock shadows in the cave, a transition space between the Hill's surface and the black hole of the cave's inner depth.

Carol Fieldhouse

Elementals at Harborough Cave

The Elementals group visit the cave at Harborough Rocks around the Winter Solstice 2016.

Four women swathed in coats, cloaks, wraps and hats - the wear of wise women who know how winter cold grips the shoulders of those who stand to observe and listen to the land. We peer into the ancient fern lined well as people have for millennia, a lantern is lit. We listen for echoes of the past as the wind scours the rocks. In the shelter of the cave more candles are lit, voices convene in a communal chant from their felt drum beat - denying the pulse, drone and clatter of the factory beyond the cave.

The view from the cave

The view from the cave

The cave entrance

The cave entrance

Read the latest blog posts by